Global Job Market Transformation: Insights from the IMF on AI

Insights | 29-01-2024 | By Robin Mitchell

Key things to know:

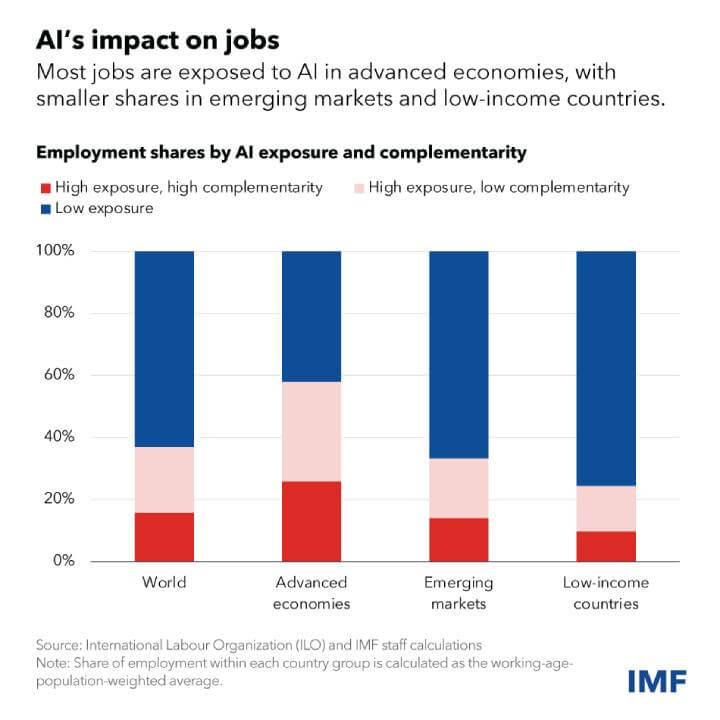

- IMF Report Highlights: Reveals up to 40% of jobs in developed countries could be impacted by AI, with a significant 20% in developing nations.

- AI's Unique Challenges: Unlike past technologies, AI presents a skewed balance in job creation versus elimination, and a substantial skill gap for transition.

- Economic and Social Implications: The report emphasizes the need for policy and educational shifts to mitigate AI's potential inequalities and labour market disruptions.

- Global Cooperation Urged: The IMF advocates for international collaboration in AI governance to ensure equitable global benefits and mitigate economic risks.

A new report from the IMF suggests that up to 40% of jobs in developed countries are at risk of being overtaken by AI, while those in non-developed countries face around 20%. Why is the introduction of AI unlike any other technology before it, what exactly does the report mention, and what ramifications could such a situation present?

Why is the introduction of AI, unlike any other technology before it?

Across all of human history, the introduction of new technologies has just about always resulted in a net positive for the species. The introduction of fire allowed early man to keep warm and warn predators, the introduction of agriculture turned us from hunter-gatherers nomads to settlers, creating large complex societies, and the introduction of iron allowed for all kinds of developments in the field of science and engineering.

But in the past few centuries, the accelerated rate of technological discovery saw many in society concerned with the ramifications that those developments could bring about. For example, the steam engine made those in manual labour positions worry as it could potentially replace them in the fields and factories. The same concerns emerged with the introduction of production lines and semi-automated machinery.

However, every time these technologies were introduced, the result was not a loss of jobs but instead a shift in jobs whereby those in the fields, mines, or workhouses would simply move into different industries or take up new positions that the new technologies generated. For example, steam engines replaced large portions of manual labour in farms, but these engines needed to be built, serviced, and operated, all of which required a large workforce.

Despite this historical pattern whereby the introduction of new technologies results in a better quality of life, the emergence of AI is causing a stir among many in the population, worried that its introduction could replace their jobs. But, according to economists, these members of society should not fret over potential job losses, as the historical trend has shown that the introduction of new technologies creates new job opportunities and higher pay.

The Unprecedented Challenges of AI Integration

While this may have been true for most technologies introduced over the years, the introduction of AI into society is fundamentally different to all technologies before it, and it is this difference that many, including economists, fail to recognise.

The biggest challenge that AI introduces is that while new job opportunities would be made, the number of jobs being eliminated vs. jobs being created is heavily skewed. A great example of this in action was the decision by Tesla to eliminate the human factor in data gathering for its learning models, replacing it with more AI, resulting in hundreds of job losses and no new opportunities.

The second challenge faced with AI is that the skill gap between the jobs it replaces and those that it creates is extremely large. With such a large gap, it is incredibly difficult for those who have been made redundant to retrain and work with AI. For example, those working in journalism whose expertise lies in language and literature will unlikely be able to learn the fundamental concepts of AI models, coding, and system management (which is ironic when considering that journalists were using the phrase “learn to code” to those in the non-renewable industry when their jobs were at threat from green policies).

The third challenge, which itself could be a serious danger, is that AI has the potential to be self-improving, and this rate of improvement could be exponential. If AI is able to take on new jobs at an exponential rate, this would lead to mass proportions of the population being made redundant, potentially collapsing the economy. As this rate of job loss could be in the years, the shock to society would be far too great, with individuals being unable to retrain fast enough.

With all of these considered, it could turn out that the introduction of AI results in the vast majority of jobs being low-skilled manual labour, with humans being the physical extension of AI. While humans wouldn’t be ruled by AI, it would mean that the only purpose of humans would be to feed the AI system so that society can take comfort in what it provides: digital content.

IMF reports up to 40% of jobs under threat by AI

In recognition of the dangers that AI could pose to the labour force and society in general, the IMF has recently published a report on their concerns relating to AI and its increased use. According to findings by the IMF, it is believed that in the near future, AI could become integrated into 60% of the labour force, with 40% being entirely replaced by AI.

Delving deeper, the IMF report not only discusses the potential job displacement but also explores broader societal impacts. It highlights the need for an inclusive approach that balances the efficiency gains from AI with the challenges of potential income inequality and social stratification. This includes policies to facilitate workforce transitions, encourage skill development, and foster an environment where AI complements rather than replaces human labour.

This figure, however, only applies to developed nations where the vast majority of labour is focused on services. In the case of developing economies, this figure shrinks to around 20%, but such a figure still represents a significant proportion of the labour force.

Furthermore, the IMF also noted that while the introduction of AI into the workforce could help improve productivity and aid employees, the number of those losing to AI would far outweigh those who benefit from it. It was also noted that while opportunities may open up with AI, there won’t be enough for everyone.

Addressing the Skill Gap and Inequality Concerns

However, the biggest concern that the IMF has relates to the potential inequality arising from those who can understand and utilise AI and those who cannot. Specifically, there are concerns surrounding the elderly population, whose skill set will be difficult to utilise in a post-AI world, while younger generations will be more readily able to adapt to changes.

These findings have also been backed up by other institutions, including Goldman Sachs, who predict that as many as 300 million jobs will be replaced by AI in the near future. As such, the IMF has called for safety nets that can help those who are affected by AI, but how that transpires into action is yet to be determined.

Furthermore, the IMF emphasizes the significance of international cooperation in managing AI's impact on the global economy. It suggests collaborative efforts in developing AI governance frameworks, sharing best practices, and ensuring that the benefits of AI advancements are shared globally. This would aid in addressing the challenges posed by AI in a unified manner, contributing to a more stable and equitable global economic landscape.

What ramifications could AI lead to?

Stopping advances in technology is rarely a good move, especially when considering that a nation that has the best AI will be at a significant advantage over others. If the US, for instance, had prevented the development of the atomic bomb, then Germany would have likely developed it first, allowing them to win the war in Europe. If the West didn’t pursue semiconductors as hard as it did, then Russian-allied nations could have taken the advantage, leading to a very different world.

The same applies to AI; if the West doesn’t develop it first, then it is likely that nations such as China, Iran, and Russia will develop these first, and considering that these countries have a fairly poor track record, their advantage in AI would hardly yield positive results.

However, if checks are not brought in for regulation of AI in the workplace, then serious economic issues could arise from large portions of the population not working. As AI wouldn’t be able to handle all needs, society would be split into those who can work with it and those who can’t, which would lead to major imbalances in society.

One solution around this would be to introduce a VAT on AI so that work generated by them provides government revenue and, from that revenue, provides a universal basic income. The advantage of such a system is that eliminating human labourers only provides marginal advantages as the value produced by the AI would be taxed, and the money being given to the population is generated as a result of AI.

Thus, companies that raise their prices to account for the UBI would end up paying more tax on those sales, thus paying citizens more money. But even then, funding such a system would be challenging, and trying to determine the value that AI brings to a business can be hard to quantify.

Overall, there is clear evidence that AI poses a major challenge to society, and if we allow it to be used unchallenged, then we risk harming not only the economy but also civilisation as a whole.