5 Things You Need to Know about Coronavirus Testing

Articles | 20-04-2020 | By Gary Elinoff

In writing this article, I have the most wonderful “problem” that any science or engineering writer can possibly have. And that is, developments in this area are happening so fast that actual progress may well have surpassed the content of this article by the time you read it!

1- What are Nucleic Acid-Based Tests?

These are extremely sensitive tests that look for direct evidence of the presence of COVID-19 (Corona Virus). The virus has a genetic pattern that is by now well known. By employment of a process called reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), that genetic pattern, if present, is detected. This confirms the presence of the virus in the patient.

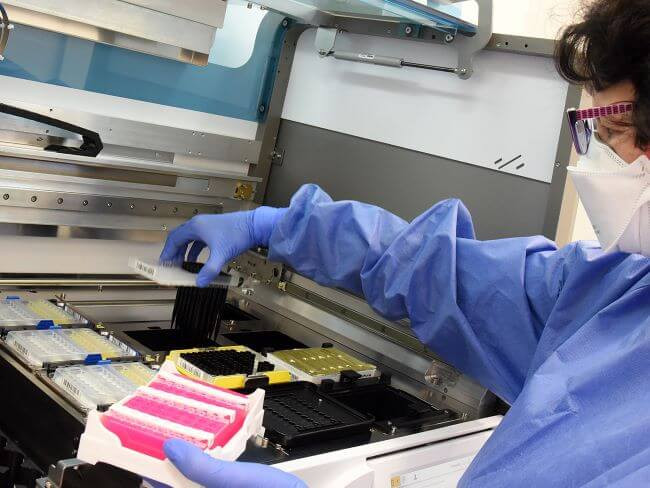

A technician at the St. Georg Hospital in Saxony prepares patient samples for PCR testing in Saxony.

Credit: IEEE Spectrum

PCR is a well-established technology. Most machines are large, centrally located, often take some time to provide results. However, Abbot Labs has developed its ID NOW machine to provide results within minutes. The device employs an isothermal amplification technology that eliminates the need for some of the more troublesome steps needed in classical RT-PCR systems.

Abbott’s ID Now.

Credit: Abbott

As reported by Abbott, the FDA has approved the ID NOW for use in testing for COVID-19. The ID NOW device weighs 6.6 pounds. It is described by Abbott as about “the size of a small toaster”.

2-What are Immunoassays?

An immunoassay doesn’t look for the virus. Instead, it looks for proteins produced in the body in response to the virus. These are known as antibodies, raised by the body to fight infections such as COVID-19.

Antibodies have structures that are analogs to the virus. In a kind of “lock and key” arrangement, the antibody locks up the viral antigen, rendering it harmless. The antigen-antibody combination is then removed from the person by other body systems.

Immunoassays provide “bait” in the form of an antigen, to capture to relevant antibody. The presence of the antibody in a patient’s blood confirms the fact that they have been hit by COVID-19, and that their body has responded to the threat by producing antibodies to fight it.

Antibodies take time to develop in response to a threat, and they often persist long after the threat has passed. Thus, this type of test is more useful in determining if an individual has had the infection, rather than if they have recently been infected.

At the time of this writing two facts are important to note:

-

Medical experts are debating whether the presence of antibodies to COVID-19 confer immunity, and if so, for how long.

-

Immunoassay tests are cropping up from numerous sources. Many are untested and of dubious value

3- What is CRISPR?

CRISPR is a technique for altering genetic material in living cells. It can also be used to identify genetic material in viruses.

As reported by NPR, scientists at UC San Francisco and Mammoth Biosciences have developed a test for COVID-19 that will deliver results in 30 to 45 minutes. According to the UCSF’s Dr Charles Chiu, he and his colleagues expect to submit the test to the FDA during the week of April 20.

CRISPR testing will nor require expensive or sophisticated equipment.

Credit: NPR

According to Chiu, unlike other more complex systems, "I can run it now myself at home." He does caution that it will require some expertise to conduct it. He also hopes to eventually produce “handheld, pocket-sized devices using disposable cartridges." Chiu envisions devices home-based test that can be used by nonexperts.

4- The Nasal Swap Shortage

Yes, a shortage of nasal swabs. A nation that getting ready to establish a permanent presence on the moon is now suffering from a lack of ability to produce nasal swabs in sufficient quantities.

But, never fear, as reported in Statnews, on Thursday, April 16, “the Food and Drug Administration announced that it would allow a broader range of swabs to be used in tests, including some made of polyester that should be far easier to manufacture.”

And US Cotton, the country’s largest cotton swab manufacturer, has risen to the challenge. They’ve developed a polyester-based swab is compatible with testing for COVID-19.

The FDA has more to say on the subject. It has deemed that a sample can now be legitimately collected by the simple act of circling the swap in the nose. This has two positive, important consequences.

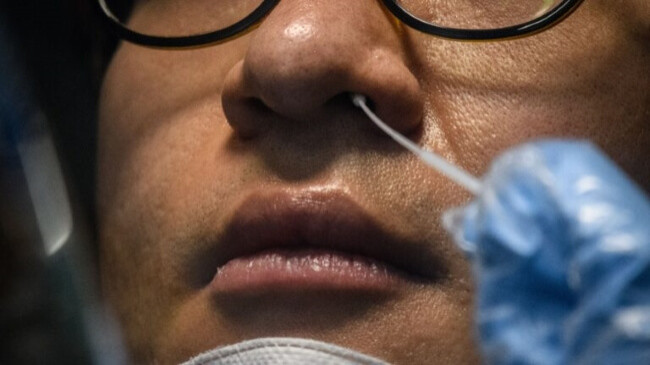

A current method involves working a swap through the nostril, deep into a patient’s throat, illustrated below.

Gathering a sample for a COVID-19 test.

Credit: Statnews

Not a lot of fun for the patient, nor the for the health care worker. The patient is likely sneeze, requiring staff to don full protective gear.

The second part of the plus side is that the patient can do this by themselves, and literally mail the sample in to be tested.

5- Conclusions

There are shortages of ventilators, and that is understandable and perhaps forgivable. Ventilators are extremely complex devices that must be manufactured to rigidly exacting standards – no shortcuts allowed.

But what isn’t understandable or forgivable is that the ability to manufacture cotton swabs and devices as absurdly simple as face masks seems to be beyond our ability.

If the governments of the world learn nothing else from this whole sorry episode, it’s the danger inherent in “just in time” manufacturing and inventory that leaves no room for flexibility in times of emergency. And while we’re at it, let’s also condemn supply chains that stretch, literally, from here to China that do not allow for the ready availability medical protective gear that’s only slightly more complex than rain ponchos.

Read more articles related to the Coronavirus pandemic:

- How Are Electronics Being Used in the Fight Against the Coronavirus Pandemic?

- Disinfection Robots Battle COVID-19 Spread

- A Wireless and Wearable Polymer Temperature Sensor for Healthcare Monitoring

- Microfluidic Technology May deliver Cheap, Easy Coronavirus Test

- A Look at the Ventilators Used During the Coronavirus Pandemic