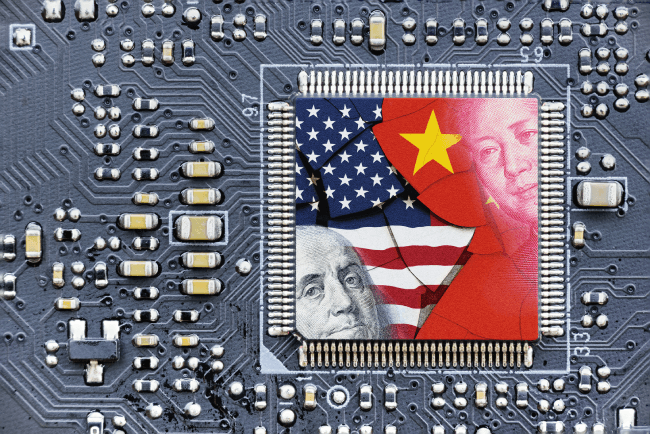

Huawei's Defiance: Mate 60 Pro Reveals Tech Trade War Loopholes

In The News | 28-09-2023 | By Robin Mitchell

A deep dive into the Huawei Mate 60 Pro components reveals surprising findings. As the US continues to try to limit Chinese access to key technologies, the latest Huawei Mate 60 Pro not only has 7nm components but also integrates South Korean RAM modules, something that should have been entirely inaccessible to China. What challenges has the West faced in its sanctions, what was discovered in the Huawei device, and is it time to stop the semiconductor trade war?

What challenges has the West faced in its sanctions against China?

The ongoing semiconductor war between China and the West started with good intentions: preventing Chinese hardware from becoming dominant in critical infrastructure, protecting Western security interests, and encouraging China to end its practice of violating IP laws. However, what started out as a few restrictions on hardware quickly escalated into a tit-for-tat battle, with each side introducing additional restrictions.

While the West has been fairly confident that it has achieved some of its goals (especially preventing China access to 7nm tech), recent developments in China put a stop to any celebration. China's tech advancements amidst trade restrictions showcase the nation's determination and resourcefulness.

Firstly, the decision by China to restrict exports of gallium and germanium saw the prices of these materials rapidly increase. As these materials are essential in the manufacture of next-generation technologies such as GaN transistors, China has managed to get itself into a position to interfere with Western technological development.

According to a recent report by CNN, SK Hynix, a renowned South Korean chipmaker, is delving into how its memory chips found their way into the Mate 60 Pro. This discovery has raised eyebrows in the tech community, given the stringent export controls in place.

“The significance of the development is that there are restrictions on what SK Hynix can ship to China,” G Dan Hutcheson, vice chair of TechInsights, told CNN. “Where do these chips come from? The big question is whether any laws were violated.”

Secondly, the revelation of 7nm devices in Huawei’s latest smartphone, the Mate 60 Pro, has demonstrated that the restrictions placed on China have failed. As most thought that ASML EUV systems were the only machines capable of such technology, the US decision to restrict Chinese access to such hardware was considered to be a done deal at stopping China. However, the new processor used in the Mate 60 Pro, manufactured by SMIC, has clearly demonstrated this is far from the case.

These two cases are but a few examples of how China has managed to continue developing its technology in spite of Western sanctions. While the semiconductor war may have yielded positive results at the beginning, forcing China into a corner may not have been the best move by the West. The ongoing semiconductor trade war implications are evident as tensions between China and the West escalate. The US-China tech sanctions have been a focal point in the global tech industry, with both sides showing resilience.

These instances highlight the global semiconductor supply chain challenges that nations face amidst political tensions.

RAM modules found in Huawei phones that should not be there

The unexpected discovery of South Korean RAM in Chinese smartphones, particularly the Mate 60 Pro, has raised numerous questions. The revelation of 7nm technology in the Huawei Mate 60 Pro phone was shocking enough to the world, but further analysis of the smartphone has also revealed components that should have been impossible to use. Specifically, the devices in question are memory modules manufactured by SK Hynix that are subjected to strict export controls by South Korea and the US. Huawei's sourcing of restricted components, such as the SK Hynix memory chips, has baffled experts.

The SK Hynix memory chips controversy has added another layer of complexity to the ongoing tech disputes. The RAM module found in the device was an LPDDR5 12GB variation, while the NAND flash was found to be 512GB in size, and the resulting news surrounding these chips has been a fall of almost 4% in SK Hynix stock price. It is likely that the fall in stock value is a result of investor concerns that SK Hynix could face fines for a potential breach of trade law.

"Shares in Hynix fell more than 4% on Friday after it emerged that two of its products, a 12 gigabyte (GB) LPDDR5 chip and 512 GB NAND flash memory chip, were found inside the Huawei handset by TechInsights, a research organization based in Canada specializing in semiconductors, which took the phone apart for analysis." (CNN)

According to SK Hynix, the company hasn’t shipped any devices to China since the US introduced restrictions against Huawei in 2020. Currently, SK Hynix hasn’t responded to questions regarding the discovery, but they have mentioned that an investigation is being launched to try and figure out how China was able to get the devices.

Industry experts have speculated that Huawei might have procured these memory chips from secondary markets or had a stockpile from before the US export restrictions became stringent. This revelation underscores the complexities and potential loopholes in the global semiconductor supply chain.

Some suspect that the devices were old stock, whereby Huawei purchased a large number of devices just before the trade restrictions came into play. However, storing semiconductors for an extended period of time introduces a number of challenges, including solderability and reliability. Furthermore, devices put into storage will quickly become technologically inferior to new devices being released, so Huawei storing large numbers of devices in 2020 would have been a bet against Chinese semiconductor developers.

Is it time to stop the semiconductor war?

Considering that China already has 7nm technology, one must wonder if the semiconductor war against China is still worth continuing. If the goal of the war was simply to prevent Chinese devices from being used in critical infrastructure, then that is something which can easily be done with local legislation.

In fact, if the semiconductor war was to end today, it could actually have a negative impact on the Chinese economy and numerous semiconductor investments made. By allowing China access to 7nm devices manufactured by foundries such as TSMC, all the investments made by the Chinese government and the semiconductor industry would no longer become cost-effective (as it would be cheaper to get devices abroad).

In order for China to protect its own interests, its government would then have to ban the import of foreign sub 14nm devices, forcing itself to develop its own industry (as so much investment has already been put into it). This could potentially lead to a sunken cost fallacy, as the Chinese government pours money into foundries to try and develop its own independent technologies.

As the situation currently stands, China is still unable to access sub-7nm technology, and this is important to prevent China from developing next-generation military technologies. Eventually, China will find solutions to its semiconductor problems, and this may be sooner rather than later, thus raising the question, “is it time to stop the semiconductor war”?

As reported by Yonhap News Agency, SK hynix Vice Chairman Park Jung-ho reaffirmed that the company ceased all business interactions with Huawei post the US chip sanctions in 2020. The company is committed to adhering to the US government's export restrictions, highlighting the global ramifications of the semiconductor trade war. The impact of export controls on global tech has been profound, with both sides feeling the repercussions.