Chocolate vs Electronics? When It Comes to Beating Strokes My Money's on Both

17-06-2015 | By Paul Whytock

As a committed consumer of dark Swiss chocolate, research saying that downing a daily helping could reduce the risk of cardiac disease and increase stroke prevention came as very good news to me.

Researchers at the University of Aberdeen have concluded that eating up to 100g of chocolate daily lowers the risk of stroke by an impressive 23%. This latest news comes several years after scientists found that chocolate helped reduce blood pressure, a major contributing factor to stroke attacks.

I am totally in favour of consuming a healthy level of daily chocolate and adding chocolate to the list of foods for stroke patients but, I believe technology will ultimately win the day when strokes happen.

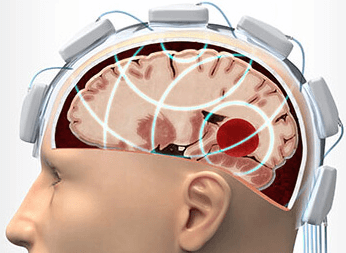

The portable microwave tomography stroke detection device

Unsurprisingly, the electronics at the core of an innovative and important system called Strokefinder could be making a massive contribution to the successful treatment of stroke victims.

Developed by Medfield Diagnostics AB, a Swedish medical technology company, Strokefinder MD100 is a portable microwave tomography system that can distinguish between ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes.

Most of us know that the rapid detection and diagnosis of a stroke is crucial in successfully treating a stroke victim. Very often, stroke victims are rushed to the hospital and then have to have MRI scans before a timely diagnosis is made. Basically, this all takes too much time.

Over 80% of strokes are ischaemic, which are caused by clots, and the remainder are caused by internal bleeding in the brain. Getting a fast and accurate diagnosis of what type of stroke is happening is crucial because only then can the correct treatment strategy be applied. For example, thrombolytic therapy is suitable for treating ischaemic strokes but is totally inappropriate, to the point of being lethal, in cases of haemorrhagic stroke.

Recognising different types of stroke

Strokefinder scores because it can recognise the different types of stroke, and because it is a portable system fitted to the patient's head, diagnosis can happen in the ambulance before reaching the hospital, thereby saving vital time. Test results usually take about ten minutes.

How does it all work? The system uses microwave tomography, which is sufficiently sensitive to differentiate between the dielectric properties of blood and brain tissue. It uses a USB/wireless interface, and the helmet-like section placed on the victim's head is connected to a laptop. Embedded software then starts the test, collates the data and analyses the results. An algorithm evaluates the polarisation, amplitude and phase of microwave signals as they pass through the brain. Changes in signal constellations due to conductivity and permittivity gradients in the brain are detected and analysed. This information is compared with stored reference data, determining whether an ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke has occurred.

This piece of kit is undoubtedly a hugely significant breakthrough when it comes to both saving victims' lives and reducing the debilitating effects of severe strokes.

According to King's College London, strokes in the United Kingdom cost the economy about £7 billion annually, and the figure for Europe as a whole is €27billion, with the United States having a total cost of $34billion. Such a system like Strokefinder has very positive implications for stroke victims and could seriously contribute to reducing national healthcare costs.

Getting back to the non-electronic treatment regime to reduce the incidence of strokes I mentioned at the beginning, precise data on how much chocolate consumption would contribute to significant healthcare cost reductions is not currently available. However, clearly, this should not deter any of us from implementing long-term field trials!